Preface:

This article was originally written in 2001 and had a large impact that was subsequently seen in numerous scientific papers. The article is presented here with only minor changes to be more timely. Namely you'll notice the term "Isurus" is still used to refer to the Extinct Mako Shark lineage. This genus has now officially been changed to "Carcharodon" in the scientific community. More will be discussed on my reasoning for sticking with "Isurus" following the article.

Communication Gap in Paleontology: Bridging Professionals and Collectors/Dealers

There's generally a lack of communication between professional and amateur collectors/dealers, and new ideas are published and "made into scientific law" by a select few. Although well-intentioned and done by well-respected individuals, the professionals generally don't have access to the bulk material from all areas needed to make completely informed decisions. Amateur collectors/dealers (99.9% of the fossil community) will often have better "common knowledge" and will have seen a wider variety of fossil material. This is the untapped mine of information from which I draw my conclusions in the following article.

Purpose of the Article: Dispelling Myths and Encouraging Debate

My reason for writing this new article is to share my personal findings and feelings on the evolution of the modern Great White Shark and to hopefully further the general body of knowledge on the subject in the scientific community (or at least spark some healthy debate, which is sure to come as this has always been a very touchy subject). I also wish to completely dispel the myth that the modern Great White evolved from the megalodon shark. Is the proper way to do this to write this paper, publish it in a scientific journal, and subject it to peer review - yes? Is that what I am doing? No. Because I think there is no way to "win" with the opinions on this one as set in stone as they seem to be (on both sides). So please enjoy the read and form your own decisions - just because it is written does not make it absolutely correct. However, it is 100% accurate as to what I believe based on my decades of experience in dealing with fossil specimens of all ages from all areas of the world. Any comments are welcome as always.

Debunking the Megalodon Connection:

The modern Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is by far the largest and most feared predatory shark alive today. This shark has been known to reach lengths of up to 20+ feet and weigh as much as 2.5 tons. The details on this shark are amazing.......but they can certainly be found elsewhere. What this article is concerned with is WHERE they came from and what impact they've had on other shark species since their arrival.

Contradictory to common knowledge, the Great White did NOT evolve from the enormous Carcharocles megalodon. The megalodon was a dead-end when it died out somewhere around 3-3.5 million years ago. Other than the fact that both the megalodon and the Great White had large serrated teeth, there are absolutely no common characteristics nor are there "transitional" features between their teeth. "Transitional" is a term used synonymously with "evolving," and it means that it shows aspects of both the new species and the old species from which it was evolving. Great White teeth are much smaller and thinner (even when comparing teeth of the same size), they have no enamel band (bourlette/chevron) on the display side, and they have larger serrations than comparable teeth from the meg. Simply put, these are two distinctly different animals.

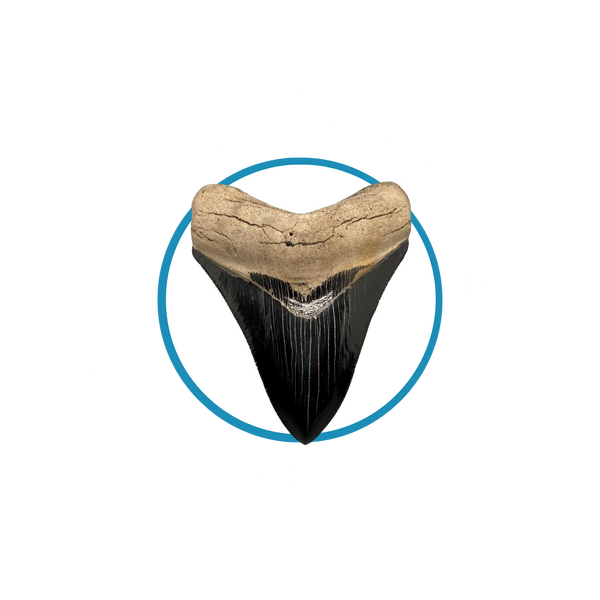

Above - This shows the different tooth structures between the Great White (Carcharodon carcharias, left) and Carcharocles megalodon (right). Both teeth are 2" long but the Great White is from a large adult shark (appx 15 feet long) and the megalodon is from a small juvenile. It can't be shown in the picture but the megalodon is almost 3x as thick as the Great White.

Above - Left - 5 1/2" (typical size for an adult) Carcharocles megalodon tooth (Miocene, California). Right - 2 1/2" (near maximum size for a huge adult) Carcharodon carcharias Great White Shark tooth. Another picture to show the distinct differences in the two species.

Ancestral Roots: Extinct Mako Sharks and the Early Evolution:

So from which shark did the Great White evolve? To find the answer you need to go back about 50-55 million years ago to when the first of the Extinct Mako Sharks came into being. This was a species known as Isurus praecursor which lived during the Eocene and probably the Early Oligocene epochs. This is the "grandfather" of all of the Mako species, both living (extant) and extinct. During the Oligocene epoch, a couple separate forms of Makos began to take shape.

One was Isurus desori which would prove to be a very wide-reaching species and the next step toward the Great White. The Great White lineage got a huge kick in the Early Miocene when Isurus hastalis was born out of I. desori. Back then the teeth from this species were not real large and seldom exceeded 2". This age of hastalis is often-referred to as the "narrow-form" because the teeth were not as wide for their length as the later version of this shark. Throughout the Miocene this species evolved slightly larger sizes.

Above - 1.70 - Isurus desori - Fossil Shortfin Mako Shark - Early Miocene (18-22 million years old) - Ica, Peru

Above - 2" upper anterior tooth and 1 3/4" upper anterolateral tooth - Isurus hastalis - Extinct Mako Shark (Narrow-form) - Middle Miocene (13-15 million years old) - North Carolina, USA. Smooth cutting edge.

Evolutionary Experiment: The Failed Serrated Mako (Isurus escheri):

By the middle Miocene (very roughly about 8-10 million years ago), a very strange thing happened with the "narrow-form" I. hastalis. In the Atlantic Ocean (and from the fossil record ONLY in the Atlantic Ocean), one group of the narrow-form Extinct Makos began to evolve very fine serrated cutting edges. The term Isurus escheri was coined to name this odd species of finely serrated Makos. Fossil teeth from this species have only been found in Mid-Late Miocene deposits in Europe (Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, etc.), and (in a couple of extremely rare instances) in South Carolina, USA. The rarity along the Atlantic Coast of the United States is probably because of a general lack of fossil deposits of this particular age - most are either older or younger. South Carolina is fortunate to have one small fossil layer of this age exposed in the Southeast corner of the state. As a sidenote - a few million years before this in the Pacific Ocean another species of Extinct Mako briefly evolved. This species was called Isurus planus and is restricted to the Middle Miocene (somewhere around 13-15 million years ago) fossil deposits from the Pacific Ocean (fossils have been found in California, Mexico, Argentina, and Japan). This species did not survive past the Middle Miocene at latest.

Above - 2" upper anterior tooth - Isurus escheri - Extinct Mako (Narrow-form, serrated) - Mid-Late Miocene (appx 8-10 million years old) - Holland. Very difficult to see (as always on this species) but this tooth has extremely fine/weak serrated cutting edges.

Above - Isurus planus - Extinct Hooked-Tooth Mako - Middle Miocene (appx 13-15 million years old) - Sharktooth Hill, Bakersfield, CA

Unfortunately, nature's first experiment with the serrated Great White failed and Isurus escheri died out shortly after it evolved. One of the reasons for the failure of this species may be that the very weak serrations simply weren't efficient enough to make a substantial difference. Perhaps the main reason was the further evolution of the main branch of narrow-form Makos. About the same time as the failed serrating attempt, the narrow-form Makos began to evolve much larger sizes and a different tooth shape. This is where the "broad-form" Isurus hastalis comes to life.

Rise of the Broad-Form Extinct Mako:

During the Late Miocene, the broad-form Extinct Mako had teeth that reached a huge 3 1/2" in length and were much wider than the previous form. The shark itself probably reached a maximum length between 25-28 feet. This form appears in fossil deposits literally worldwide - a testimony to the success of this evolutionary path.

During the Early Pliocene (very roughly 4 - 5 million years ago - this date is difficult to nail down), one isolated population of the Extinct Makos began to slowly evolve serrated edges on their teeth. This change took place off of the West Coast of the Americas and is seen in the fossil record from Southern California, Mexico, Peru, and Chile. Nowhere else in the world is this evolution noted despite the existence of countless fossil deposits of this same age.

Above - 1.56" upper anterio-lateral tooth - Isurus hastalis - Extinct Mako Shark (Broad-form) - Late Miocene (appx 5-6 million years old), Peru. Smooth cutting edge.

Serrated Evolution and Global Expansion:

Nature managed the evolution of serrations a bit differently this time. The smooth-edged broad-form Extinct Makos slowly began evolving large serrations instead of the extremely fine serrations like those found on teeth of I. escheri. Typically these transitional teeth (Carcharodon hubbelli) show serrated cutting edges near the root but blend into ill-defined serrations or even a smooth cutting edge near the tip. The serrated cutting edges would have given the evolving Great White the opportunity to go after different fatty prey items such as seals and whales (which continue to be the main prey today). Interestingly enough, the area where the Great Whites evolved (Pacific Coast of the Americas) was an area extremely rich in both seals and whales.......prey previously hunted almost exclusively by the larger megalodon sharks. The serrated cutting edges would have also allowed the Great White to use less energy during feeding. It's much easier to cut a steak with a steak knife than with a table knife!

Above - 2.31" upper intermediate tooth - Carcharodon hubbelli - Transitional Extinct Mako (Broad-form)/Great White Shark - Early Pliocene (appx 4-5 million years old), Peru. Partially serrated cutting edge.

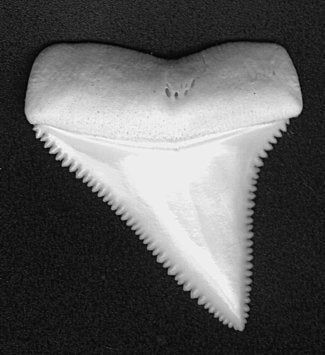

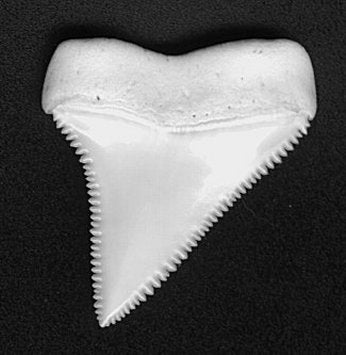

In a short period of time (perhaps as "little" as one million years or so), the broad-form Extinct Mako had fully evolved into the modern Great White (Carcharodon carcharias). Great White teeth have very large and coarse serrated cutting edges - otherwise they are almost exactly identical to the broad-form Isurus hastalis Extinct Mako from which they evolved. The size of the teeth are almost identical (fossil versions of the Great White have been found up to 3 1/2" in length), the shape and thickness are the same, and they have the exact same tooth positions (including the controversial third upper "intermediate" tooth which bends back toward the center of the jaw and is roughly two-thirds the size of the teeth on either side of it).

Above - 1 1/4" upper lateral teeth showing a modern (recent) Great White from Australia and a 4-5 million year old Isurus hastalis (Broad-form Extinct Mako) from Chile.

Above - 1 3/8" lower lateral teeth showing a modern (recent) Great White from Australia and a 4-5 million year old Isurus hastalis (Broad-form Extinct Mako) from Chile.

Above - 1 1/2" upper lateral tooth - Carcharodon carcharias - Great White Shark - Recent, Australia. Tooth from a modern shark.

Above - 2.75" upper anterior tooth - Carcharodon carcharias - Great White Shark - Late/Middle Pliocene (Appx 3 million years old), Peru. Fully serrated.

The Global Spread :

So the fossil record clearly shows that the Great White evolved from a line of Extinct Makos and not from C. megalodon. But if only one isolated population (Pacific Coast of the Americas) of the Extinct Makos evolved into the modern Great White Shark then why are Great Whites found all over the globe now? This is perhaps the most interesting aspect of the evolution of the Great Whites. After they had fully evolved in the Pacific, they began to slowly spread throughout the world. Fossil records from the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Europe show no fossil specimens from the Great White until at least the Middle Pliocene (appx 3 million years ago). All fossil Great White teeth found in these areas are true Great Whites (fully serrated) and show no evidence of transitional characteristics. Fossil Great White teeth are widespread by the Late Pliocene in all areas.

Impact on Megalodon, Extinct Mako, and Other Predatory Sharks:

The impact the Great White had on existing shark species was enormous. The first real victim was (in part, at least) the mighty Carcharocles megalodon. When Great Whites began spreading into areas inhabited by the megalodon, the population of megalodon sharks soon fell. By the Mid-Late Pliocene (probably appx 3 million years ago) the megalodon was extinct. Certainly the Great White was not the sole reason for the disappearance of the megalodon but it probably played a role. Great Whites would have been fierce competition with young megalodon sharks for food. It is entirely possible that Great Whites were faster and better equipped to catch the smaller prey (seals, etc.) that the juvenile megalodons relied on. A depletion of prey animals would lead to fewer young megalodon sharks surviving to adulthood. In a catch-22 situation, fewer adults would naturally produce fewer offspring and the circle would continue. Since the probability exists that more Great Whites could inhabit a specific area than could the megalodons, this could have been a definite problem for the largest sharks of all time.

The next victim of the Great White was (interesting enough) its own predecessor.........the Extinct Mako, Isurus hastalis. The Extinct Mako survived on until the very Late Pliocene but it too would become extinct. More than likely the serrated version (Great White) was a more efficient predator (having expanded its diet to include different types of prey) and there was simply no room for the Extinct Mako. About the same time in the Late Pliocene, the other species of large predatory shark (Parotodus benedeni), also went extinct. The benedeni was a sister group to Carcharocles megalodon (evolving from the same ancestors about 60 million years ago) but was more of an open-ocean species and always much less commonly seen. The Great White probably played a role in the demise of the benedeni (which reached lengths of probably 25-28 feet) in much the same manor as it did the megalodon and Extinct Mako.

Above - This shows the larger sizes attained by Great White Shark teeth in the past. Left - 3" upper anterior tooth (Peru, 2-3 million years old). Right - 2 1/2" upper anterior tooth (Australia, recent) - Tooth is about maximum size for Great Whites today.

Conclusion:

The evolution of the Great White Shark has had an enormous impact on marine history. It thrived in an era of even larger sharks and contributed to their demise. Today the Great White is found worldwide and is one of nature's true wonders. No other shark sparks the inner fear of humans like they do nor draws the most protection from those same humans. Hopefully, they will be around as the apex predator in their domain until something better evolves to take its place - that is nature's way.

Postscript : Isurus vs Carcharodon

As noted in the introduction the scientific world has now adopted the genus "Carcharodon" to refer to some of the ancestors of the Great White. The reasoning behind the name is obviously solid as the proof of lineage is irrefutable at this point. In the past (David Ward personal communication) I also expressed my support for changing the name of hastalis to "Carcharodon". However recent events (namely the seemingly absurd change of Carcharocles megalodon to Otodus megalodon) have caused me to reconsider my support. I believe there are two main reasons that Carcharodon should be used solely for the Great White (and the transitional Great White).

One is the evolution of serrations. This is such an important evolutionary change that basically allowed the Great White to becoming the top predatory shark in the oceans. It's prey changed, behaviors changed, and as a result the whole marine world changed.

Secondly - this is a rare case where the evolution of one shark did not mean the end of the old species. "Carcharodon" hastalis discounts the fact that the evolution of the Great White happened in only an isolated population of hastalis. Not all hastalis evolved into Great Whites and, in fact, these animals survived alongside each other for at least a million years.

Isurus hastalis is an important species and is a side branch of the modern Makos (Isurus oxyrinchus and paucus). We feel Isurus is still valid and we will continue to use this name.

Copyright Note:

Copyright © 2001, 2023, Steven A. Alter, www.megalodonteeth.com - Special thanks to Lutz Andres and Christian Guevarra who gave constructive criticism and other invaluable input.